Casa Sabor’s supper clubs continue to celebrate Latin American food and culture by hosting two evenings to mark Dia de Muertos (The Day of the Dead), one of the two most significant religious festivals in Mexico, the other being Easter. We wanted to explain to those who might not know what the Day of the Dead means to Latin American communities. For this we turned to our good friend Dr Paul Holmes, retired psychiatrist and psychotherapist, keen though non-professional anthropologist, and former long term resident of Mexico. This is what he had to tell us:

Whilst Easter celebrations directly involve whole communities, with in some villages there being dramatic re-enactments following the time scale of the trial and crucifixion of Jesus, the activities associated with Dia de Muertos are more focused on the home and the family and remembrance of the dead who have left the family, if only in body but not soul.

The importance of the day of the dead, and the associated beliefs and customs, were built upon the complex ideas and values of the pre-Hispanic Mexican population. The dead were seen as needing celebrating not mourned. Family altars, or ofrendas, were created, usually in the home, but sometime communally, to honour and remember the dead. It is almost as if death, rather than being a conqueror, was a positive ally to be celebrated with a feast and a fiesta. Death and associated sculptures and carvings were a dominant feature of pre-Colombian art.

Over time these pre-Hispanic celebration or feasts became linked to the Christian festival of All Saints (November 1st) and Souls Day (November 2nd), which were already a cultural absorption of the Celtic and pagan autumnal ceremony of Samhain, This marked the time when the Celts believed that the boundaries between the living and the dead became blurred, the point of the year when autumn shifted into winter, This festival was already the result of Celtic beliefs merging with the Roman festival of Pomona, the Roman goddess of trees and fruit, only then to be appropriated by Christian doctrines.

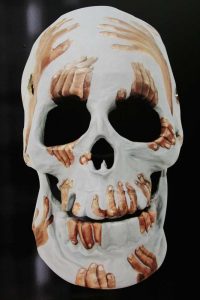

These pre-Hispanic and pre-Christian autumnal ceremonies continue to be marked in Mexican society by the Dia de Muertos. The family altars or ofrendas created in the home (and sometimes the street) vary in styles and character, home by home and region by region. But there are some common features: there may be photographs of someone whose death is being marked, samples of foods or drinks that the dead person liked; the altar decorated with bright orange marigolds (cempasuchil) together with sugar skulls and paper mache skeletons (calacas), symbolism with a very clear associations with their pre Hispanic origin. The focus on skulls and skeletons, features of pre-Colombian culture, rituals and ceremonies (including sometimes human sacrifices), have deep roots, just as All Hallows Eve (All Hallows Eve) has morphed in Halloween, again with a focus on skulls, death and feasting (this time with European roots).

The complex process whereby a community integrates the old culture with the new continues apace, All Hallows Eve now being taken over by Mammon (the mediaeval demon of wealth and greed) both in Europe and Mexico.

Casa Sabor will celebrate this complex history with two supper clubs in early November. There will be calacas and sugar skulls, but no ritual sacrifices are planned!

Recent Comments